How LLMs are trained for function calling

A journey through the history of tool use methods

Why should LLMs be any good at function calling, and what techniques have model builders used? Investigating this leads to surprisingly unsatisfactory answers: many model papers provide no details at all, or only the tiniest hints at their methods. If you’ve landed here trying to answer that question yourself, I hope this post gives you a starting point for your own search.

In my prior post I looked at how tool use—now commonly implemented through a function calling paradigm—is an increasingly important capability for LLMs. Here I’ll describe in more detail how function calling works at the model layer, tying together a history of methods into a loosely chronological narrative.

Zooming out, some of the foundational trends were:

LLMs became good at natural language tasks

Building LLMs with a hardcoded set of tools available

LLMs became good at code, JSON, etc., from a disproportionate presence of those forms in their corpuses

Instruction tuning of LLMs

Testing LLMs on arbitrary tools, through zero-shot prompting

Building LLMs to support arbitrary lists of tools as functions

It’s not quite right to describe these as sequential innovations, but it’s also not quite right to consider them happening equivalently in parallel. Instead I look at those as loosely ordered and overlapping.

Customizing LLMs for tools

The core of an LLM is a next-token predictor.1 You can think of it as a function with well-defined inputs and outputs:

Input: A series of prior tokens (typically, but not necessarily, bounded)

Output: Probabilities for the next token

When you use an LLM in a chat interface or an API, it calls the function and generates output in a loop, appending prior output to its input. Model providers usually supply a long list of parameters to control that loop algorithm. This class of autoregressive LLMs was initially trained purely to optimize next-word prediction (e.g., OpenAI’s GPT-2 in 2019).

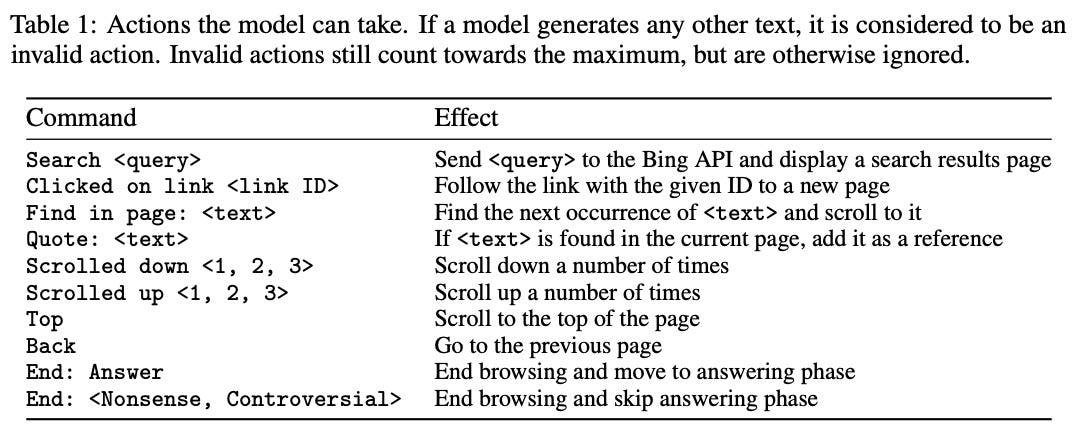

One approach to incorporating tools into LLMs is to optimize for individual tools like calculators or Wikipedia querying. An early example is Giving BERT a Calculator: Finding Operations and Arguments with Reading Comprehension (2019) [1]. That used a question-answer dataset that the authors annotated with custom tool calls for a set of mathematical operations. Stepping forward a few years, another early example is WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback (2022) [2].2 The idea here is to give the LLM a search engine, human label a corpus with search engine calls, and then fine-tune the model (which the authors—at OpenAI—explored with several methods). Human labeling in this sense means updating the corpus to contain additional text in select places.

A major downside of these approaches is the finite tool set, including the effort needed to define it. Knowing the correct tool answers is another limitation; the popularity of calculator tools in early papers couldn’t have been hurt by the easy verification of calculator operations. Designing and building these models was a lot of work, yet those custom capabilities didn’t necessarily generalize to additional tools or different base models.

Foundations for generalized tool use

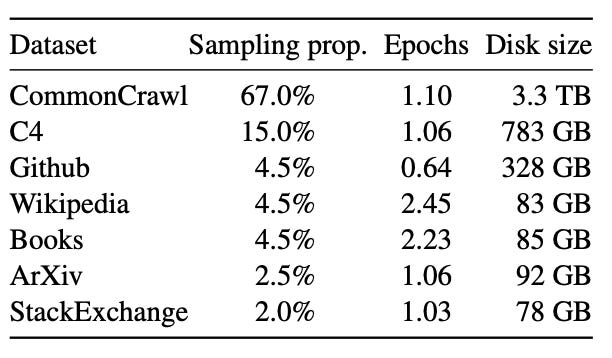

While the early emphasis of LLM development was to generate realistic (and predominantly English) language outputs, it became increasingly clear that this was not at all incompatible with competence at code creation or other tasks. LLMs were trained on large internet corpuses which contain a lot of code and other structured outputs. Developers started intentionally adding code corpuses alongside general internet text. Adding diverse sources increased generalization abilities without hurting language skills.

Understanding code syntax is an important foundation for expressing tools as functions. Meanwhile, LLMs became good at following instructions. Model builders (e.g., OpenAI) accumulated large samples of conversational data, some labeled via thumbs-up/thumbs-down feedback in the UI. They started to update models with “post-training” phases. A key paper here is Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback (2022) by OpenAI [4]. Notably, that predates ChatGPT, and it relied on paid labellers evaluating OpenAI’s responses to API query requests. Instruction tuning usually came at the cost of worse next-token prediction (naturally, since this degraded the primacy of next-token prediction as the optimization goal), but it increasingly made LLMs more conversational and better at following commands.

Models became shockingly good at human-like text generation and increasingly competent at related skills like code generation. Conversational text would no longer be the boundary for these models. GPT-3 changed the world, even if most people didn’t realize it until ChatGPT.3 It was so good that curious people wondered: Can I just tell it that I have tools, without any custom training or prior knowledge of those specific tools? In plain text in my prompt? Will that work?

Well, it was worth a shot. One notable example is how Nat Friedman shared natbot, which defines a few browser controls like “CLICK X - click on a given element. You can only click on links, buttons, and inputs!”. That’s just included in the prompt, without any of the corpus labeling or custom training used by methods like WebGPT.

LangChain then quickly followed with a programmatic interface around this method of zero-shot tool use. That was all the way back in version 0.0.19, in the same month ChatGPT was released.

Altogether this pivot into zero-shot tool use was another instance of the bitter lesson: “General methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective.” [5]. After years of hand-labeled data and fine-tuning, we could instead just use a stronger model and use text input to describe a set of tools and the format for using them.

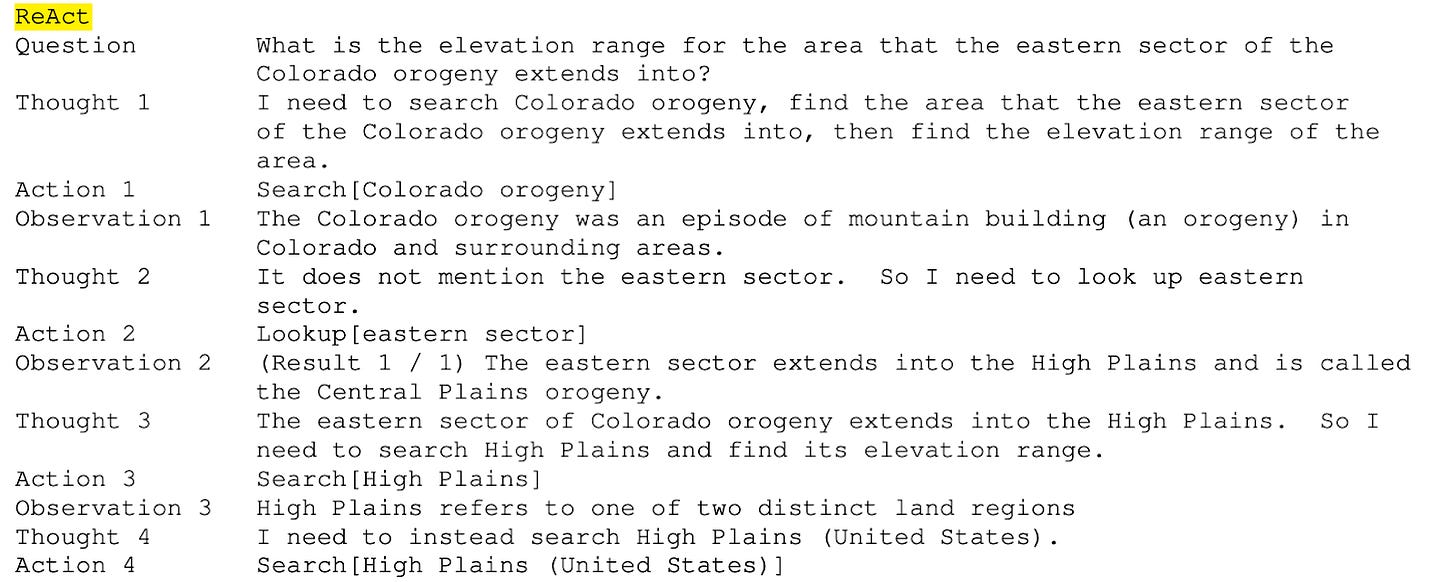

ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models (2022) is another notable paper from this time, and is one of the most cited papers in the tool use literature [6]. It provided a set of basic tools, such as Wikipedia access.

The main insight of ReAct isn’t directly about tool use methods, but rather that we can merge reasoning and acting, combined with instruction-tuning to form an effective pattern for tool use.

Moving to function calling

And then in one fell swoop, OpenAI changed the paradigm entirely.4

From their announcement, Function calling and other API updates:

Developers can now describe functions to gpt-4-0613 and gpt-3.5-turbo-0613, and have the model intelligently choose to output a JSON object containing arguments to call those functions. This is a new way to more reliably connect GPT’s capabilities with external tools and APIs.

These models have been fine-tuned to both detect when a function needs to be called (depending on the user’s input) and to respond with JSON that adheres to the function signature. Function calling allows developers to more reliably get structured data back from the model.

Instead of users specifying tools in English within their prompt, all tools (from the user point of view) were now to be specified as function definitions and through API parameters rather than conversational text. The models were fine-tuned to be good at handling many complex definitions.

Being the market leader, OpenAI was able to set the paradigm for others to follow, and to set a new standard that generalized tool use would be a capability of leading models going forward. That OpenAI could pull this off complicates any simple bitter lesson narrative. We can have our strong model and fine-tune it for tool use.

But how does OpenAI do it? Well, we don’t know. Because OpenAI doesn’t provide many model details anymore. They did not explain how they customized the models or how they integrated tool use into their prompts. But we can look at some papers and open models to see how other people have done it.

A scalable approach to learning tools

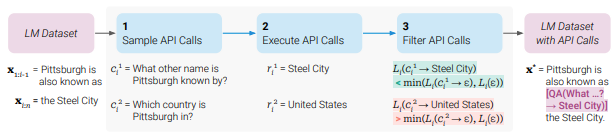

Let’s look at ToolFormer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools (2023), a very influential paper which laid out a formula for applying tools to a corpus without hand-labeling [7].

The approach is:

Start with an initial model and corpus

Ask an LLM to pick questions and insert calls to tools

Execute tool calls

Measure usefulness by effect on predicting subsequent text

Keep only helpful calls

Fine-tune on this new corpus

Worth noting: A similar formula was present earlier in TALM: Tool Augmented Language Models (2022) [8].

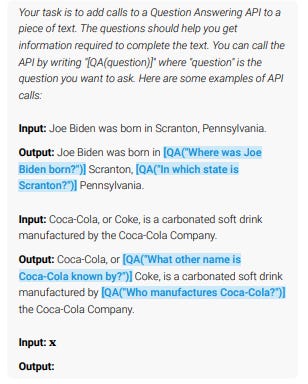

The ToolFormer approach was to prompt LLMs to create tool calls, with one prompt for each of 5 tools.

A good prompt and model will generate many plausible tool calls, but we can be a bit more precise in deciding which ones to retain in the corpus. They compute a weighted cross-entropy of subsequent tokens for: (a) no API call, (b) API call without an answer, (c) the API call with its answer, and then keep only cases where improvement passes a threshold.

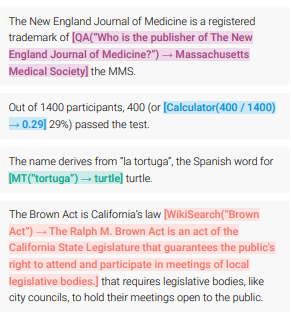

After running the text through the prompt and its response, and then filtering, the text to fine-tune on ends up looking like this (without the colouring and boxes, of course):

The model learns that it needs to output strings like “[Calculator(400 / 1400)] ->”, at which point (in inference) the system calls its calculator and appends “ 0.29]” to the text before continuing with the inference loop.5

User-supplied functions

Note that ToolFormer has a big limitation: it has a pre-defined, small number of tools. We need an approach that generalizes to user-defined tools, and ideally with them specified as functions. NexusRaven: A Commercially-Permissive Model for Function Calling (2023) has a description of such a method [9].

The approach is:

Start with a large corpus of code

Use an LLM to generate descriptions for each function

Use an LLM to create natural-language queries that would use those functions, with a CoT reasoning trace leading to each use

Include a list of other similar candidate functions, so that the model has to discriminate carefully6

Fine-tune

The approach is similar to, and indeed cites, ToolLLM: Facilitating Large Language Models to Master 16000+ Real-World APIs (2023) [10]. When successful, this method should force the model to be adaptable to using any custom provided functions.

We can see the influence of that method even a couple of years later in The Llama 3 Herd of Models (2025) [11]. Their method—albeit very vague described—sounds a lot like NexusRaven: “More precisely, we extract function calls and their definitions, clean and filter them, e.g. for missing docstrings or non-executable functions, and use Llama 3 to generate a natural language query corresponding to the function call.”

Now that we’re in the realm of user-supplied tools, we should address how those tools are specified to the model. When we had a small finite list of tools (à la ToolFormer) the model could memorize each specific tool in fine-tuning. We can’t do that for run-time specified tools.

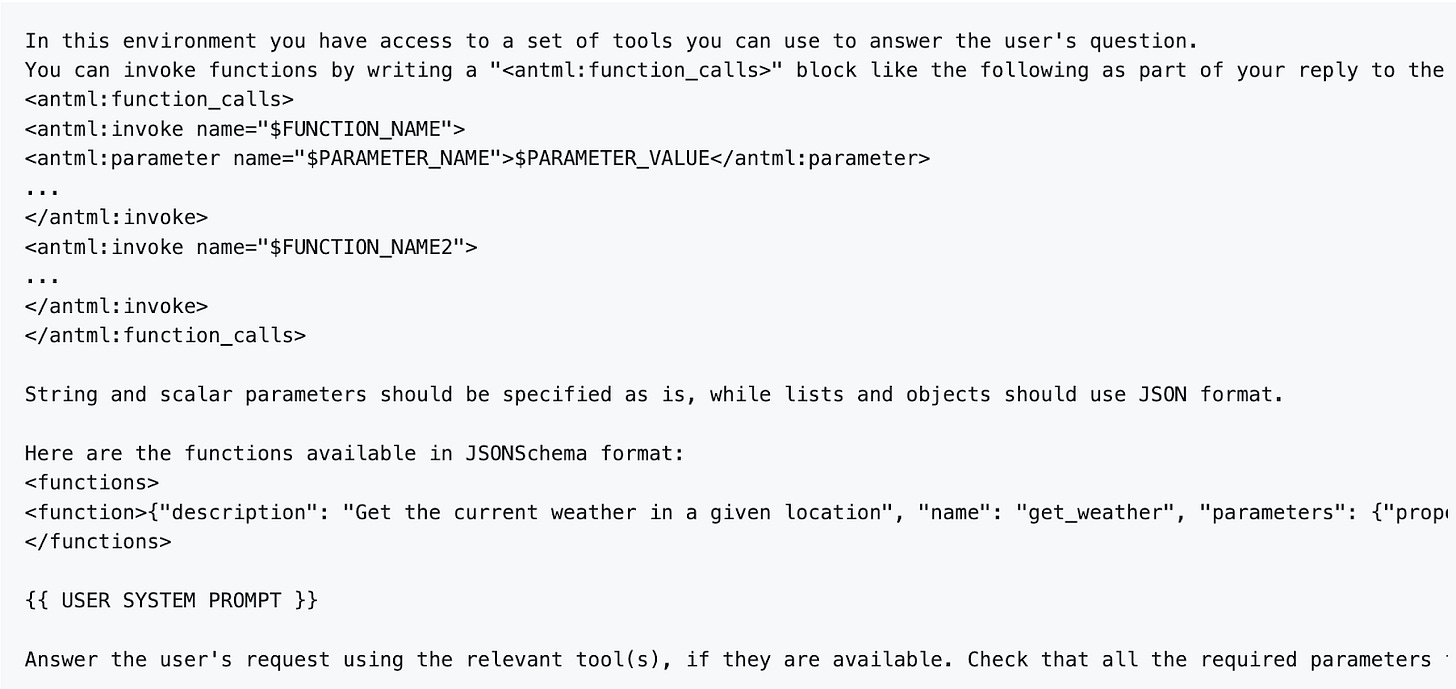

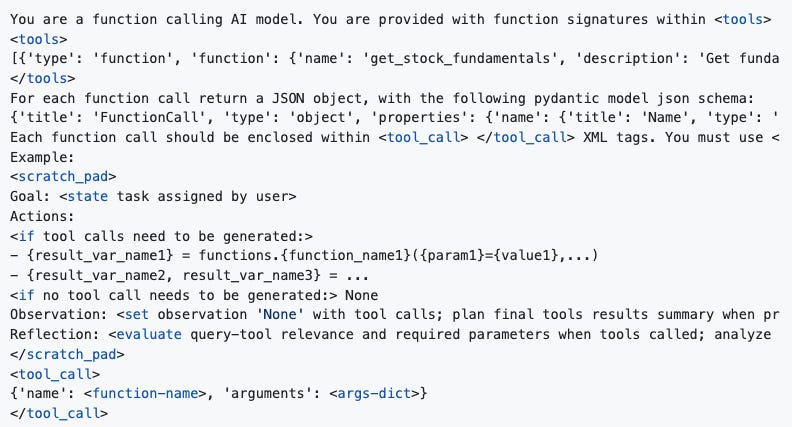

Note that the API structure for OpenAI or other providers is not itself an answer to how those tools are specified at the model layer. Remember, an LLM processes a sequence of text tokens7. Tool definitions—along with user prompts, assistant responses, and everything else—all need to be flattened into one text. Even with these logically separated at the API layer, ultimately they are combined into a big stream of text.

We don’t truly know what happens behind the API for closed models, but we can see some examples from leaked prompts or known open source models. The pattern seems to be JSON within XML blocks. See the two examples below, from one closed model and one open model.

Performance on complex tasks

So far the methods we’ve discussed either only inject tool use into an existing corpus that is otherwise unaffected by the tool call, or—aside from ToolLLM—use prompts to generate single calls for tool use. However, agentic uses make it increasingly important to support multiple tool calls in a session. Furthermore, even human use of LLMs may adaptability from each tool call.

Besides, everybody wants to be at the top of the scoreboard, and the favoured scoreboard for function calling, named Berkeley Function-Calling Leaderboard (BFCL), heavily emphasizes multi-step calls.8

The xLAM 2 series of models scores highly on BFCL; at time of their release they were the scoreboard champions (their two models “achieve the top 2 positions on the leaderboard with overall accuracies” for BFCL v3) [12]. They didn’t score exceptionally high in the other categories (and do quite poorly in some such as the agentic, memory, and live scoring metrics), but they do very well on multi-turn reasoning.9 Their method involves extensive data augmentation. They generate tasks, necessary tool calls, and entire (and entirely fake) human-agent conversations fitting those tasks. They use extensive LLM verification to improve dataset quality.

Careful data collection and augmentation may be the current frontier for tool use performance. If you look at the current top 20 on BFCL, along with the aforementioned xLAM 2 models, many of the leaders are from the most prominent model builders (e.g. Anthropic, OpenAI, and Google). One particular model stands out from that crowd, notable for its high performance on multi-step tool use and even higher performance on live queries (third overall, still!) despite being a one-off release from an independent producer. That’s watt-tool-70B.

They haven’t even released a paper to go with their strong model. Fitting with the methods known from other leaders, the limited documentation on huggingface emphasizes “a specialized dataset designed for tool usage and multi-turn dialogue” that uses “CoT techniques to synthesize high-quality multi-turn dialogue data”. It’s hard to guess at what gives them an edge, but I do find it notable that the company behind that model produces a chat-based “workflow building tool”. They have skin in the game with a direct need for an effective tool use model, and might have a good proprietary tool use corpus.

Connecting the dots

Function calling is an essential capability of modern LLMs. It’s supported by a foundation of pre-training datasets that contain extensive code examples, such that LLMs can inherently understand function definitions and the expected outputs of tools. Leading LLMs must support a dynamic user-specified set of tools, calling them accurately and at useful moments. LLMs are now fine-tuned to be effective at this skill, with text corpuses that are modified to include function calls.

Altogether, the formula is:

Extract function calls and function definitions from a reference corpus

Use LLMs to generate natural language queries where those function calls would make sense

Include tool definitions in the prompt

Choose a structured format for those definitions

Optional: Include irrelevant functions

Filter generated tool calls by usefulness

Optional: Multi-stage LLM verification

Even better: Include inherently human-annotated data from the product

Include reasoning steps (in CoT, ReAct, or more flexible formats)

Fine-tune on the corpus

This history of tool use has twists and turns, with several methods that have lost and then regained prominence. These methods weren’t added to the formula one-by-one, but rather they have been tested in different combinations. This suggests that new methods could very well emerge that change everything yet again.

[1] Andor, D., He, L., Lee, K., & Pitler, E. (2019). Giving BERT a Calculator: Finding Operations and Arguments with Reading Comprehension. ArXiv, abs/1909.00109.

[2] Nakano, R., Hilton, J., Balaji, S., Wu, J., Long, O., Kim, C., Hesse, C., Jain, S., Kosaraju, V., Saunders, W., Jiang, X., Cobbe, K., Eloundou, T., Krueger, G., Button, K., Knight, M., Chess, B., & Schulman, J. (2021). WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback. ArXiv, abs/2112.09332.

[3] Touvron, H., Lavril, T., Izacard, G., Martinet, X., Lachaux, M., Lacroix, T., Rozière, B., Goyal, N., Hambro, E., Azhar, F., Rodriguez, A., Joulin, A., Grave, E., & Lample, G. (2023). LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. ArXiv, abs/2302.13971.

[4] Ouyang, L., Wu, J., Jiang, X., Almeida, D., Wainwright, C.L., Mishkin, P., Zhang, C., Agarwal, S., Slama, K., Ray, A., Schulman, J., Hilton, J., Kelton, F., Miller, L.E., Simens, M., Askell, A., Welinder, P., Christiano, P.F., Leike, J., & Lowe, R.J. (2022). Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. ArXiv, abs/2203.02155.

[5] Sutton, Rich (March 13, 2019). “The Bitter Lesson”. www.incompleteideas.net. Retrieved October 15, 2025.

[6] Yao, S., Zhao, J., Yu, D., Du, N., Shafran, I., Narasimhan, K., & Cao, Y. (2022). ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models. ArXiv, abs/2210.03629.

[7] Schick, T., Dwivedi-Yu, J., Dessì, R., Raileanu, R., Lomeli, M., Zettlemoyer, L., Cancedda, N., & Scialom, T. (2023). Toolformer: Language Models Can Teach Themselves to Use Tools. ArXiv, abs/2302.04761.

[8] Parisi, A., Zhao, Y., & Fiedel, N. (2022). TALM: Tool Augmented Language Models. ArXiv, abs/2205.12255.

[9] Srinivasan, V., Dong, Z., Zhu, B., Yu, B., Mao, H., Mosk-Aoyama, D., Keutzer, K., Jiao, J., and Zhang, J. (2023) Nexusraven: A commercially-permissive language model for function calling. NeurIPS 2023 Foundation Models for Decision Making Workshop.

[10] Qin, Y., Liang, S., Ye, Y., Zhu, K., Yan, L., Lu, Y., Lin, Y., Cong, X., Tang, X., Qian, B., Zhao, S., Tian, R., Xie, R., Zhou, J., Gerstein, M.H., Li, D., Liu, Z., & Sun, M. (2023). ToolLLM: Facilitating Large Language Models to Master 16000+ Real-world APIs. ArXiv, abs/2307.16789.

[11] Meta.10 (2024). The Llama 3 Herd of Models.

[12] Prabhakar, A., Liu, Z., Yao, W., Zhang, J., Zhu, M., Wang, S., Liu, Z., Awalgaonkar, T.M., Chen, H., Hoang, T., Niebles, J., Heinecke, S., Wang, H., Savarese, S., & Xiong, C. (2025). APIGen-MT: Agentic Pipeline for Multi-Turn Data Generation via Simulated Agent-Human Interplay. ArXiv, abs/2504.03601.

Not all LLMs, but all of the ones we’re talking about.

It continues to shock me how quickly modern AI is developing, that a paper from 2022 can be considered “early” from my vantage point in 2025.

Here’s where we need the obligatory William Gibson quote, “The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed”.

Well, there were a couple of preliminary swoops in the prior months as OpenAI explored a plug-in model.

Confusingly, in the paper they use both brackets (“[“, “]”) and XML tags (“<API>, “</API>”). But they have a footnote that clarifies that the XML tags are just for readability (my hunch is that they changed their mind somewhere along the way and couldn’t be bothered to update the pretty visuals in the paper.

The description in the paper is a little too succinct for me to be confident on exactly how it works, so I could very well be wrong in my interpretation.

Setting aside other modalities like images without loss of generality.

BFCL routinely changes how it measures models. In the current criteria at time of writing, v4, multi-turn reasoning directly contributes 30% of the score. Plus there is also some multi-turn use under the other categories.

Be careful to pay attention to specific BCFL categories if you want to choose between models. High variance in the multi-step category leads to it having a significant effect on the resulting ordering.

Author listed as “Meta”, with an appendix of hundreds of contributors.